Trusting Strangers—The Paradox of the Sharing Economy

By Bipin Suresh, Director of Engineering, Airbnb |Nov 01, 2021

How can a transportation company own no vehicles, a vacation rental company own no homes, and a food delivery company own no kitchens? Sharing economy companies thrive in this apparent contradiction. But with no assets, what is their core invention? What caused the birth, and how did they survive a pandemic that forbade person-to-person interactions? Bipin Suresh, Director of Engineering, Airbnb, examines how these companies navigated these challenges, and are now paving a path towards a new kind of economy.

My plane touched down in Bengaluru's international airport at 2 AM. Tired from a strenuous 16-hour flight from San Francisco, I searched for my phone, still half asleep—not to inform my family of my safe arrival, but to open up Uber. I stared with bleary eyes at a screen informing me that within minutes, ‘Nagaraj (4.85 stars)’ would pull up at the curb in a white car and drive me home. I had never met Nagaraj before.

Over the next week, I similarly trusted many strangers to make life easier and better: I had a stranger deliver my “death by chocolate” ice cream from the famous “Corner House” using Zomato. I had a plumber fix a leaky faucet using Urban Company. And I found yet another stranger to fill my allergy prescription via PharmEasy. When I handed a carefully wrapped package to my Dunzo courier who had just arrived at my gate, I couldn’t help but ask myself: how had such a tectonic change occurred so suddenly?

The Birth of a New Kind of Economy

Over the last decade, there has been an explosion of these “sharing economy” companies—peer-to-peer marketplaces that allow individuals to exchange goods and services with each other. This new kind of economy is in stark contrast to the one ushered in by the Industrial Revolution, where individuals bought not from other individuals, but from large corporations with mass production, mass distribution, and hierarchical organisations. What led to this sudden transition? I posit three major factors:

First, there is the proliferation of the internet and smartphones. Today, almost two out of every three people in the world have access to the internet.[1] Coupled with the growing availability of smartphones and cheap data, more and more people are able to escape the tyranny of geography, reach escape velocity, and launch themselves into the global economy.

The internet has enabled everyone to become a global entrepreneur. You can publish a tweet that delivers greater insight than an op-ed piece in The New York Times, upload a video on YouTube that reaches more people than a Hollywood blockbuster, or teach a class on Udemy that educates more people than Harvard does in a decade. All you need is a smartphone.

Second, the growing dominance of urban living. In 2020, the United Nations reported that a majority of the world’s population now lives in urban areas.[2] When you live in a city, you live in a sharing economy. You share parks, subways, and apartments. Sharing isn’t a foreign concept to you anymore—it is already a part of your life.

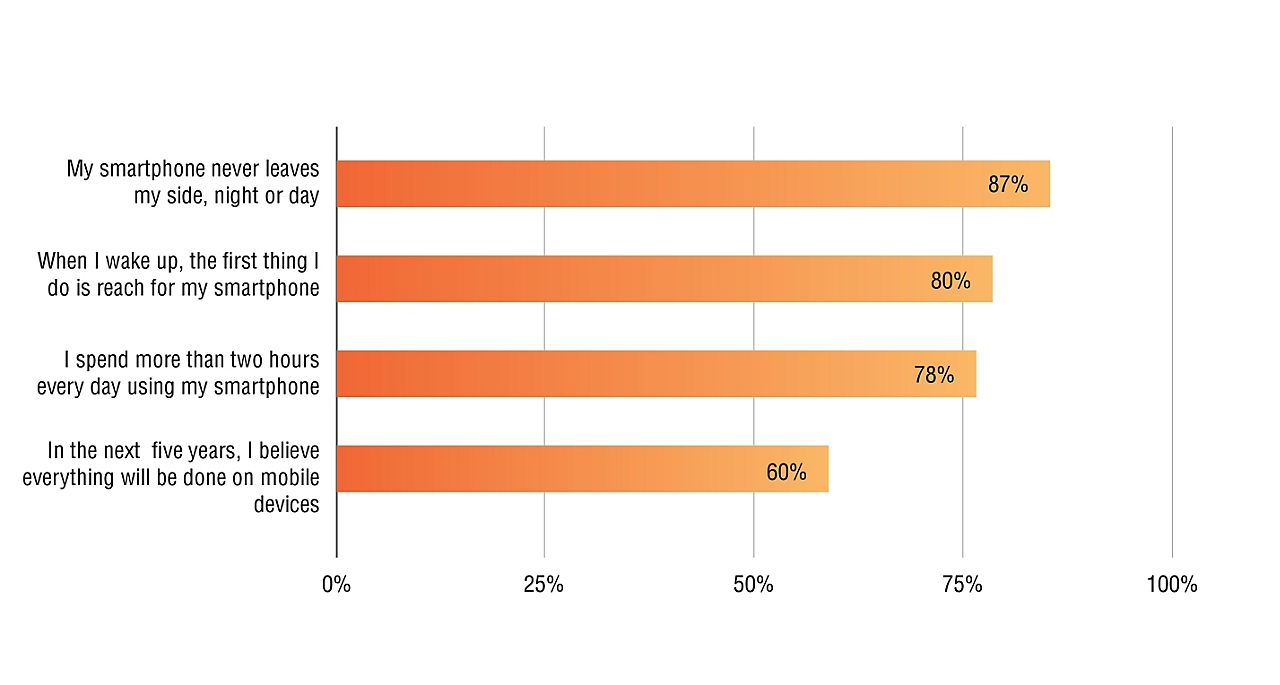

Third, we have a final and surprisingly subtle factor at play: with declining birth rates and longer life expectancies, millennials are the largest generation in the U.S. labour force today.[3] This generation is the first of ‘digital natives’, growing up with the internet. A whopping 87% of millennials in the US report[4] that “their smartphone never leaves their side.” 80% state, “when I wake up, the first thing I do is check my phone,” something that I shamefully admit to as well. And in one shocking survey, millennials report they prefer one perk over pensions, cash bonuses, and free healthcare—flexible work hours.

Millennial Smartphone Behavior, USA

Source: Internet trends 2015, Mary Meeker @ KPCB, citing Zogby analytics – www.kpcb.com/InternetTrends

Oftentimes, when I ask my Uber drivers why they choose to drive for Uber, many of them talk about the freedom to work when they want and under what terms. In a world that’s becoming increasingly individualistic, being your own boss is the ultimate perk.

This confluence of pervasive connectivity, access to a global economy, low barrier to entry, destruction of information asymmetries, move to cities, and a desire for flexibility has led to an unprecedented growth of the sharing economy. These combined factors set companies on the road to becoming a major part of our global economy. People expected tremendous, continued growth—more than a 20x increase from US$14 billion in 2014 to US$335 billion by 2025.[5]

Then, in March 2020, the world changed.

What Doesn’t Kill You Only Makes You Stronger

Many predicted a global economic recession would follow the COVID-19 pandemic. And indeed, in the first few months, the doom and gloom prediction of collapse seemed to come true. Airbnb lost 80% of its business in eight weeks. A Wired article[6] asked bluntly, “Is this the end of Airbnb?” Uber’s CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, publicly stated that, “business today doesn’t come close to covering our expenses,” as the company laid off more than 6,700 employees and closed down 45 offices around the world.[7]

But the obituaries were published prematurely. Less than a year later, in its Q2 2021 earnings, Airbnb reported that they had not only recovered, but revenue had grown 10% above the pre-pandemic levels of Q2 2019.[8] Several other sharing economy companies show similar results. They not only survived the meteor of COVID-19, but have thrived because of it, leaving the old business dinosaurs—hotels, cruises, and taxi companies—on the brink of extinction.

How did they manage such an unbelievable turnaround in less than 12 months?

The world expected another Great Depression, but instead got a Great Compression. The pandemic and its lockdowns accelerated the adoption of hundreds of burgeoning technologies. The pandemic gave many people their first taste of the sharing economy: they vacationed in homes instead of cramped hotel rooms, ordered food to be delivered rather than eating at crowded buffets, and had their groceries dropped off at their doorstep instead of shopping in packed supermarkets.

Companies of the sharing economy that were struggling to cross the chasm into the early majority saw a tidal wave of new consumers. As technology-first enterprises, many of them adapted at the speed of the market. Being asset-light was a boon to these companies. They could quickly hunker down and reduce their expenses. The world did change irreversibly, but it heavily favoured the sharing economy.

Looking from the outside in, ancient businesses stared befuddled at their new competition. If these companies owned no traditional assets, what exactly was their business based on?

The Currency of the New Economy

It seems ironic, almost paradoxical, that a transportation company owns no cars, a vacation rental company owns no homes, and a food delivery company owns no kitchens. And yet, this is the reality of the Olas, the Airbnbs, and the Swiggys of the world. What, then, is the core invention of these asset-light companies?

The answer is hidden in my interaction with Nagaraj, who drove me back home from the airport that night. When we arrived at my house, Nagaraj hurried out of the car to help me unload my bags. Once done, he mumbled something almost apologetically under his breath. I assumed he was requesting a tip, but as I reached for my wallet, he repeated his request: “5-star rating please, sir?”

In a marketplace of strangers, trust plays a central, almost existential role. In the office of France’s largest ride-sharing company, BlaBlaCar, you will find a life-sized cardboard cut-out of “TrustMan,” a cape-wearing superhero with a giant “T” plastered on his costume’s chest. Airbnb’s CEO Brian Chesky often talks about how his company is “in the business of Trust.” He continues, “Our real innovation is not allowing people to book a home; it’s designing a framework to allow millions of people to trust one another.”[9]

Digitising trust is the central invention of the sharing economy. This happens in a hundred subtle ways, through ratings, reviews, profile photos, background checks, identity verifications, insurance programmes, dispute resolutions, and secure on-platform payments. If strangers aren’t able to trust each other, the entire sharing ecosystem crumbles and collapses. Trust plays such a central role that it’s tied inextricably to your identity: my name is displayed not just as ‘Bipin’ but as ‘Bipin (4.87 stars)’. When Nagaraj asked me for a 5-star rating, he was requesting a tip in the currency of peer-to-peer marketplaces—trust.

The Next Unicorn

What is the future of the sharing economy? I think the answer depends on how trust will evolve on the internet.

On one end of the spectrum, you could imagine your online trust score becoming a bigger and bigger part of your identity. Could your delivery rating on Uber Eats provide Dunzo a hint at how likely you are to deliver a package? Likely. Could one capture the notion of your comprehensive trustworthiness, so that any two individuals can check each other’s trustworthiness before they enter a transaction? Maybe.

To some, this might sound dystopian, but that future is already here. In China, the central government has taken up the role of assessor of trustworthiness. China’s “sesame credit,” a point system that builds upon familiar financial credit scores in the Western world, includes rewards and penalties for its citizens' social behaviour. Don’t pay your bills on time? You might be deemed a little untrustworthy and lose a few points. Pay them regularly, and you might be deemed to be a valuable—and trustworthy—member of society.

But I suspect that China’s solution will not port to most Western democracies. Instead, “Trust as a Service,” could become a critical piece of our infrastructure for the future internet. Similar to how Amazon built AWS, the Amazon Web Services now worth US$400 billion,[10] to provide the technological building blocks for the internet, anyone who builds this centralised, comprehensive, combined trust score stands to provide enormous value.

On the other end of the spectrum is a world completely devoid of trust. This may seem like a foreign concept at first, but imagine a world where individuals interacted with each other regardless of each other’s trustworthiness—simply because they could fully rely on legal contracts to ensure complete fairness. Then, instead of large platforms that mediate commerce, individuals would interact freely, only using an adjudicator in the unlikely event of a dispute.

Taken a step further: what if we could digitise and automate the contract and adjudicators? For example, what if a courier could prove that a package was delivered untampered without involving an expensive legal third party? Tantalisingly, the technology for these kinds of interactions is already here. Digital signatures that provide unforgeability, blockchains that record transactions immutably, smart contracts that execute autonomously, and biometrics that prove someone’s identity incontrovertibly. Today, we are witnessing these kinds of exchanges in the digital world—money as cryptocurrencies, and digital goods as NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens).

Could the future hold a pure, unhindered, and unfettered exchange of value between strangers, not just for digital goods and services, but in the ‘real world’ too? Either way, the future is exciting. We are getting ready for the demise of the corporation as a central entity in capitalism, and a return to a world where individuals are paid their true worth as decided by the ‘invisible hand’ of the market. Over the next decade, the creation of many more of these peer-to-peer marketplace ‘unicorns’—businesses valued more than a billion dollars—is inevitable.

Will you start one? Because all you need is a smartphone, an internet connection, and a way to digitise trust.

[1]Internet World Stats (2021, July 3). World Internet Users and 2021 Population Stats. Retrieved from https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm

[2] UN-Habitat (2020). World Cities Report 2020: The Value of Sustainable Urbanization. Retrieved from https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/10/wcr_2020_report.pdf

[3] Fry, R. (2020, April 28). Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America’s largest generation. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/28/millennials-overtake-baby-boomers-as-americas-largest-generation/

[4] Mitek (2014, September 25). Millennial Study: Zogby analytics. Retrieved from https://www.miteksystems.com/press-releases/millennial-study-one-in-three-want-to-communicate-by-snapping-a-mobile-photo

[5] Yaraghi, N. and Ravi, S. (2017, March). The Current and Future State of the Sharing Economy. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/sharingeconomy_032017final.pdf

[6] Temperton, J. (2020, April 22). Is this the end of Airbnb? Retrieved from https://www.wired.co.uk/article/airbnb-coronavirus-losses

[7] Dickey, M. (2020, May 18). Uber lays off another 3,000 employees. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2020/05/18/more-uber-layoffs/

[8] Airbnb (2021, August 12). Airbnb second quarter 2021 financial results. Retrieved from https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-second-quarter-2021-financial-results/

[9] Airbnb (2019, November 6). In The Business Of Trust. Retrieved from https://news.airbnb.com/in-the-business-of-trust/

[10] Trefis Team (2019, February 28). How Much Is Amazon Web Services Worth On A Standalone Basis? Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2019/02/28/how-much-is-amazon-web-services-worth-on-a-standalone-basis/

Bipin Suresh, Director of Engineering, Airbnb

Bipin Suresh establishes and leads high performing, mission-driven technology organisations. He currently leads Trust and Safety Engineering at Airbnb. He has a Master’s degree in Artificial Intelligence from Stanford University, and has over 20 years of experience in payments, monetisation, edtech, and trust. He continues to be excited about the intersection of fintech, blockchain, machine learning, and of course, trust.

?fmt=avif&qlt=100,0&resMode=sharp2&op_usm=1.75,0.3,2,0)